The function of this pseudo-religious order is to predict the cycles of tidal and celestial activity, known as tidekeeping and timekeeping, respectively. This work is conducted in cenobitic monasteries open_in_new by dedicated practitioners, then disseminated to the general populace as a community service.

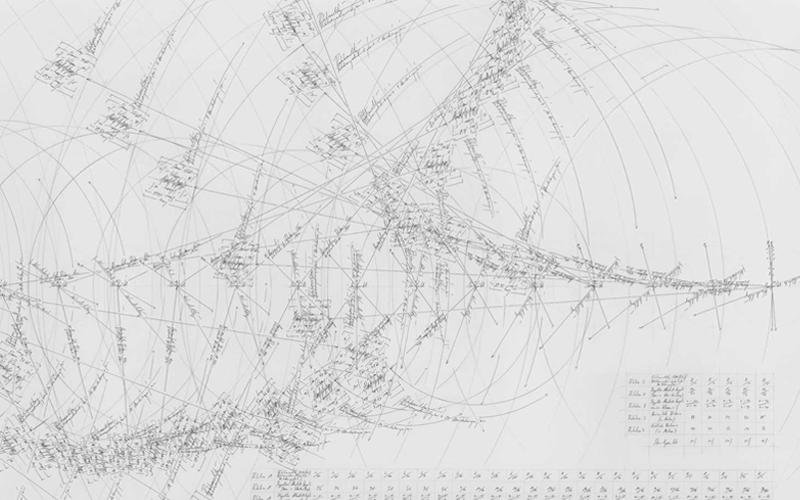

The foundation of this practice is a wealth of historical data stretching back to before the colonization of Europa. This data was originally part of advanced computing models used to model the planetary system, but at some point following the first famine the raw data was extracted to a physical medium in a bid to save it from extinction. This extraction created a dense, unintuitive record, a numerological canon whose origins have been lost to time.

This record required a great deal of mathematical discipline to decipher, and efforts continue to this day. The heart of these efforts is attempting to reverse engineer a manually applicable predictive model for tidal cycles. Different sects of the order have slightly different versions of this model, refined over years of iteration based on their beliefs and observations.

These approaches fall into two broad schools of thought, though they’re more like the endpoints of a spectrum than distinct ideologies. Exonumerism posits that the data is merely the representation of a system, and the goal of the order is to determine what that system is. In contrast, endonumerism asserts that the data is complete within itself, and that the goal of the sect is to develop a mathematical model that accurately converts between input and output. At the extremes of both these approaches, exonumerists believe that even seemingly non-cyclic events, such as human behavior, can be predicted using the same type of data analysis while endonumerists believe that the discovery of a perfect model will allow the reversal of input and output, controlling the natural world through manipulation of the numbers. The majority of practitioners fall somewhere between these two extremes, and the entire practice is ultimately a highly experimental and collaborative one.

Senior practitioners spend most of their time on research, analyzing historical and contemporary tidal data and making revisions to their denominational model. They often visit other monasteries to discuss (and vigorously debate) their latest findings and approaches. Meanwhile, junior practitioners are responsible for daily tasks such as using the current denominational model to predict upcoming tides and disseminating that information to their local community, as well as measuring and recording actual values as they compare to the predictions.

They are also responsible for tracking and marking the passage of time. In comparison to tidekeeping, day to day timekeeping is relatively straightforward since Europa has no solar variation. Nonetheless, standardized timekeeping is critical to interpreting historical tidal data in the context of the current day, keeping accurate records of contemporary tidal data, and making predictions meaningfully useful to the general populace. Timekeeping in also involves the maintenance of calendars, with exonumerists in particular marking cycles by the movement of the other Galilean moons.